When one refers to the strict literal interpretation of the terms “freedom” and “air” provided by the Oxford Dictionary, the Freedoms of the Air prima facie appears as a pleonasm. The dictionary defines “freedom” as “the absence of subjection to foreign domination or despotic government”. “Air” is defined as “the free or unconfined space above the surface of the earth”. Free as a bird, The Beatles sang. While our feathered friends such as the charismatic Canada goose may enjoy this absolute freedom, is it also the case for air carriers’ metallic birds — airliners?

The obvious answer is no. Primo, while birds may get territorial from time to time, territorial sovereignty is a fundamental concept in international law — Article 1 of the Chicago Convention (1944) reaffirms Article 1 of the Paris Convention (1919), “every State has complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its territory”. Secondo, the Freedoms of the Air are based on scheduled international air services, meaning that they only apply to air carriers licensed by a State to provide scheduled international air services (except the First and Second Freedoms, they also apply to non-scheduled flights). Tertio, as rational creatures, humans draft laws and have the wonderful capacity to negotiate and consent to agreements. Therefore, contrary to birds, humans need rules, laws and agreements mainly to enable commerce — a purely human behaviour.

Origins

One of the opening sentences of the Chicago Convention (1944) declares that it accepted the principle that every state had complete and exclusive sovereignty over the air space above its territory and it set forth that no scheduled international air service might operate over or into the territory of a contacting state without its previous consent. Two provisions of the Chicago Convention (1944) are particularly interesting for the purpose of this text: Article 5 and 6. Article 5 of the Chicago Convention (1944) authorizes certain rights of innocent passage for non-scheduled flights. In fact, aircraft engaged in non-scheduled flights enjoy the right to fly into or across the territory of another State, and to make stops for non-traffic purposes (First and Second Freedoms). However, the State flown over has the right to require the non-scheduled aircraft to land, and to follow prescribed routes, or obtain special permission for such flights. Article 6 prohibits scheduled operations except with the permission or authorization of the State in whose territory an aircraft wishes to fly, and only in accordance with the terms established by that State.

The concept of the Freedoms of the Air is therefore profoundly interconnected with commerce — commercial air transport is divided into scheduled air services and non-scheduled flights. Technological advancements of the 20th century in the aeronautical field enabled the free moving of people, goods and mail — becoming sine qua non to the growth of modern global economies. Originally, the range of commercial aircraft was limited, and air transport networks were nationally oriented. However, the technological progress made during World War II changed the theme — aircraft were flying higher, faster, and farther. In 1944, the nations of the world agreed to meet in Chicago to establish the framework for all future bilateral and multilateral agreements to use international airspaces.

The efforts of the delegates to win general acceptance of five freedoms of the air were unsuccessful, but a multilateral agreement was agreed upon — only as far as the first two freedoms: (1) the right to overfly; and (2) the right to make a technical stop. The first five freedoms are regularly exchanged between pairs of States in air service agreements.

Contrary to what one may believe, the Freedoms of the Air are not automatically granted to a carrier (airlines) as a right. Often subject to political pressures, they may be privileges in nature from time to time, and these privileges must be negotiated by parties. To be clear, all freedoms beyond the First and the Second have to be negotiated by bilateral agreements.

The Nine Freedoms of the Air

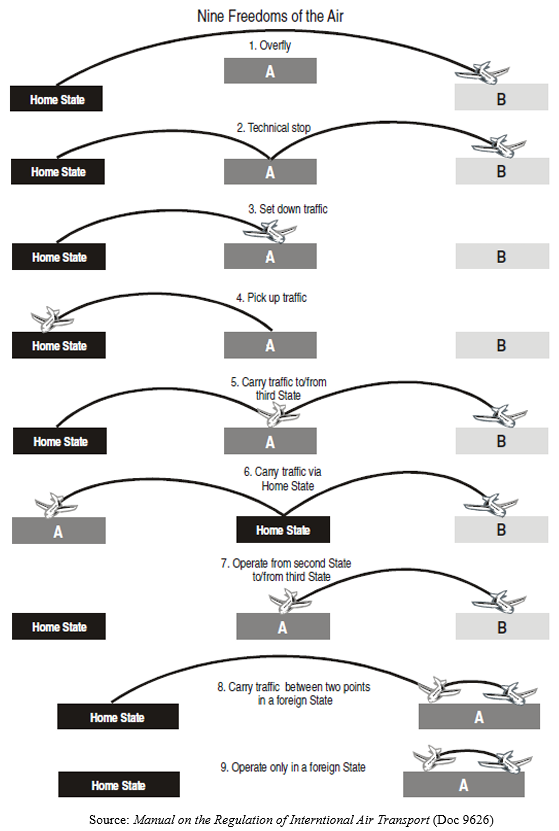

Happily, States have substantially liberalized their skies since the implementation of the Chicago Convention in 1944. Pursuant to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Manual on the Regulation of International Air Transport, — as of 2022 — there are nine different freedoms:

First Freedom — Known as “transit freedom”, this is the right or privilege, in respect of scheduled international air services, granted by one State to another State or States to fly across its territory without landing. In other words, this is the freedom to overfly a foreign State from a home State en route to another without landing. Since the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, the first freedom is widely available across the world, but nations such as Russia often limit the transit freedom to a few carriers.

Second Freedom — This is the right or privilege, in respect of scheduled international air services, granted by one State to another State or States to land in its territory for non-traffic purposes (e.g. technical or refueling). A flight from a home country may land in another State for purposes other than carrying passengers, such as refueling, maintenance, or emergencies. The final destination is a third State. For instance, in the earlier stages of transatlantic flights, a refueling stop was often required in Newfoundland (Gander International Airport — CYQX), Canada and Ireland. With the expansion of the ultra-long-hauls (e.g. airliners such as the Airbus A350-900ULR), the Second Freedom is becoming less relevant.

NOTE: All Freedoms beyond the First and the Second have to be negotiated by bilateral agreements.

Third Freedom — This is the right or privilege, in respect of scheduled international air services, granted by one State to another State to put down, in the territory of the first State, traffic coming from the home State of the carrier. Simply put, this is the freedom to carry traffic from a home State to another State for the purpose of commercial services.

Fourth Freedom — This is the right or privilege, in respect of scheduled international air services, granted by one State to another State to take on, in the territory of the first State, traffic destined for the home State of the carrier. This is the freedom to pick up traffic from another State to a home State for the purpose of commercial services.

NOTE: The Third and Fourth Freedoms constitute the foundation for direct commercial services, providing the rights to load and unload passengers, mail, and freight in another State. They are commonly reciprocal agreements implying that the two involved States will open commercial services to their respective carriers simultaneously.

Fifth Freedom — This is the right or privilege, in respect of scheduled international air services, granted by one State to another State to put down and to take on, in the territory of the first State, traffic coming from or destined to a third State. In other words, the Fifth Freedom is the freedom to carry traffic between two foreign States on a flight that either originated in or is destined for the carrier’s home State. It enables carriers to carry passengers from a home State to another intermediate State and then fly on to third-State with the right to pick up passengers in the intermediate State. The Fifth Freedom is divided into two categories: (1) Intermediate Fifth Freedom Type is the right to carry from the third State to the second State; and (2) Beyond Fifth Freedom Type is the right to carry from a second country to a third State.

NOTE: The ICAO characterizes all freedoms beyond the Fifth Freedom as “so-called” because only the first five Freedoms have been officially recognized as such by international treaty.

The “So-Called” Sixth Freedom — This is the right or privilege, in respect of scheduled international air services, of transporting, via the home State of the carrier, traffic moving between two other States. It is the “unofficial” freedom to carry traffic between two foreign States via the carrier’s home State by combining third and fourth freedoms. Not formally part of the Chicago Convention, it refers to the right to carry passengers between two States through an airport in the home State. With the hubbing function of most air transport networks, this freedom has become more common, notably in Europe (Heathrow Airport — EGLL and Amsterdam Airport Schiphol — EHAM) and the Middle East (Dubai International Airport — OMDB).

The “So-Called” Seventh Freedom — This is the right or privilege, in respect of scheduled international air services, granted by one State to another State, of transporting traffic between the territory of the granting State and any third State with no requirement to include on such operation any point in the territory of the recipient State (i.e. the service need not connect to or be an extension of any service to/from the home State of the carrier). This is the freedom to base aircraft in a foreign State for use on international services, establishing a de facto foreign hub. Covers the right to operate passenger services between two States outside the home State.

The “So-Called” Eighth Freedom — This is the right or privilege, in respect of scheduled international air services, of transporting cabotage traffic between two points in the territory of the granting State on a service which originates or terminates in the home State of the foreign carrier or outside the territory of the granting State. Also known as “consecutive cabotage”, it is freedom to carry traffic between two domestic points in a foreign State on a flight that either originated in or is destined for the carrier’s home country. It involves the right to move passengers on a route from a home country to a destination country that uses more than one stop along which passengers may be loaded and unloaded.

The “So-Called” Ninth Freedom — Known as “stand alone cabotage”, this is the right or privilege of transporting cabotage traffic of the granting State on a service performed entirely within the territory of the granting State. This is the freedom to carry traffic between two domestic points in a foreign State without a flight continuing on to an airline’s home State.